It’s obviously becoming difficult to keep track of where the US government policy is on any particular day. Last week, it was ‘Liberation Day’, which included tariffs being imposed on remote penguin colonies in the back of nowhere, then Musk labelling the Trump’s trade adviser ‘dumber than a sack of bricks’, then tariffs on Chinese goods rising to 124 per cent (which will make then uncompetitive), then the ‘pause’ on reciprocal tariffs beyond the 10 per cent level … what will be next. These shifts and decisions are not exactly benign and the US Administration is displaying the sort of incompetence, capriciousness, flippancy – whatever you want to call it – that hardly befits the largest economic nation in the globe which has its tentacles spread far and wide. I was particularly interested though in the now infamous ‘Rose Garden Liberation Day’ speech Trump made last week (April 2, 2025) where he made claims about Japan, which were used to justify the imposition of 24 per cent tariffs on that nation. According to the President, Japan is among a host of countries that have “looted, pillaged, raped and plundered” the US. His evidence? None is available. The reality is that US cars don’t sell in Japan because they are inferior and ill-suited to the market. We explore that theme in this blog post.

Trump’s evidence for the ‘looting, pillaging, raping and plundering’ by Japan was, in his own words:

… perhaps worst of all are the non-monetary restrictions imposed by South Korea, Japan and very many other nations as a result of these colossal trade barriers … Eighty-one percent of the cars in South Korea are made in South Korea. 94 percent of the cars in Japan are made in Japan. Toyota sells one million foreign made automobiles into the United States and General Motors sells almost none. Ford sells very little. None of our companies are allowed to go into other countries …

But such horrendous imbalances have devastated our industrial base and put our national security at risk. I don’t blame these other countries at all for this calamity. I blame former presidents and past leaders who weren’t doing their job.

I was interested in that claim as I have been doing some work on the evolution of the Japanese auto industry, which would appear to categorically refute the validity of the claim.

The US President followed up the ‘Rose Garden’ rant, with a meeting with the Prime Minister of Japan, Shigeru Ishiba and wrote on his Twitter Replacement that:

They don’t take our cars, but we take MILLIONS of theirs!

Then, on April 5, 2025, the White House Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy and Homeland Security Advisor, proferred a Tweet (do we still call X messages Tweets?) that is captured below (along with some fact checking from other people which is interesting).

The author of this Tweet is clearly not the ‘sharpest tool in the shed’.

His path to extreme conservatism was prompted by reading a gun control advocacy from the then boss of the NRA (Source).

As I said not the ‘sharpest’.

So let’s answer his question in relation to Japan.

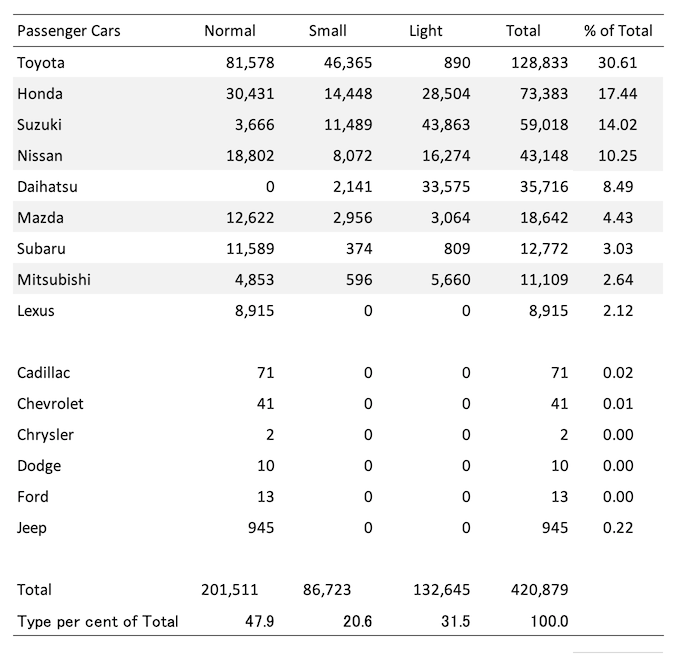

I constructed the following table from the most recent data published by the – Japan Automobile Dealers Association (JADA) – and it shows new car sales in March 2025 (published April 4, 2025) by manufacturer and type of passenger vehicle (Normal, Small, Light).

The Japanese manufacturers accounted for 93 per cent of total sales in Japan in March 2025.

52.1 per cent of the total sales are in Small or Light passenger cars and the US manufacturers produce nothing in that range.’

The US offerings are also in the larger category for which there is very limited (to say the least) demand in the domestic Japanese market.

Toyota, Honda and Suzuki account for 62.1 per cent of total sales.

So in narrow sense, Trump and his sycophants are correct.

The US manufacturers have virtually no foothold in the Japanese automobile market, which is dominated by Japanese manufacturers and demonstrates a majority preference to Small or Ultra Small (Light) cars.

Those little rectangular boxes that are everywhere in Japan.

But the reason for that is not related to restrictions imposed by Japan.

Ever since I was a student at University I have followed the so-called trade talks between the US and Japan.

The US angst about trading with Japan goes back at least that far.

There was the first – Nixon Shock – on August 15, 1971, when US President Nixon appeared on national television and announced that he was suspending the US-gold convertibility that was central to the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates.

For Japan, which had been running trade surpluses against the US since 1965, the more interesting aspect of Nixon’s announcement was the imposition of a 10 per cent tariff on imports.

The Japanese government also didn’t want the yen to appreciate much because that would worsen the impact on its external competitiveness from the tariff.

The yen was floated but the Bank of Japan intervened in foreign exchange markets to limit the appreciation.

It was this decision that introduced the term ‘dirty float’ to the economics lexicon – courtesy of the West German Economics Minister, Karl Schiller who thought it was a retrograde strategy by foreign governments to undermine Germany’s trade position.

Soon after, he ordered the Deutschbank to follow suit (Source).

Attempts at restoring the fixed exchange rate system (the so-called Smithsonian Agreement of December 1971) failed and by 1973 the Bretton Woods system was finally laid to rest, even though the European countries continued with fixed rates for reasons I explained in my 2015 book

– Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015).

The US government understood that the Japanese authorities would do everything to prevent the yen from appreciating too much (in their eyes) and regularly pumped erroneous information (yes, fake news!) into the ‘markets’ about further likely appreciation, which they then used as a bargaining lever to gain more access to the Japanese market.

Yes, Trump did not invent the use of deliberate global chaos as a bargaining chip.

The US pressured the Japanese government to allow more imports into Japan from the US and restrict exports from Japan into the US.

It is a well-worn road.

The early 1970s ‘textile war’ between the US and Japan was another beachhead for the US authorities who demanded Japan restrict their exports of “certain synthetic and woolen textiles to the United States’ (Source).

The Japanese textile manufacturers refused to accept quotas.

The US claimed the “The textile issue is a fuse … If it explodes there will be a hell of a lot of damage to things beside textiles. If we have an economic confrontation with Japan it would quickly spread to politics as well. There is a lot at stake.”

At the time, the textile industry was “Japan’s biggest employer .. and accounted for some 10 per cent of Japan’s gross national product”.

You can copy and paste China these days into text about trade from the 1970s that mentioned Japan.

The US has just shifted ‘trade enemies’.

In the 1960s, as part of the post-WW2 reconstruction of Japan, the Japanese government imposed tariffs in Japan for car imports – the ‘infant industry’ justification.

At the time, the car manufacturers in Japan were small in scale and had not yet achieved the unit costs that the large US manufacturers had achieved.

Tariffs of between 30 and 40 per cent, depending on the size of the car, were put in place, in addition to domestic sales taxes on cars (of between 15 and 40 per cent).

Higher tariffs and taxes were levied on larger vehicles because the Japanese wanted to discourage purchase of them for obvious reasons (geography, density etc), which, of course, worked against the US manufacturers.

So this was a major point of disagreement between the US and Japanese governments in the early 1970s and was behind the US demands that the yen be allowed to appreciate and that the Japanese authorities should introduce export controls.

By the mid-to-late 1970s, the Japanese manufacturers had effectively run out of domestic demand for their vehicles and pressured the government to abandon the export controls with an eye to selling more into the large US market.

The political climate in the US at the time (Carter as President) was firmly opposed to trade protection and as a consequence Japanese car exports into the US boomed.

In the ensuing negotiations, the Japanese government abandoned the tariff on car imports in 1977.

The data shows that foreign vehicle imports jumped by 16 per cent in July 1978 when the tariff decision took effect.

But in absolute terms the numbers were small.

US cars just didn’t cut it in the Japanese market despite the now free entry.

The thirst for cheaper Japanese imports by US consumers also meant that the trade balance worked in Japan’s favour (if you think in mainstream terms).

The OPEC shocks in the 1970s also fundamentally altered the terrain for car manufacturers.

In Australia, the big 6-cylinder yank tanks disappeared almost immediately from the streets in 1974-75 and consumers shifted to smaller, Japanese built cars that had better fuel economy.

During Reagan’s presidency the tensions about the car trade imbalance were rehearsed regularly.

Cut and past Trump for Reagan in the latter’s speeches and you see the claims then have not really changed.

With the import tariffs gone, the US attention shifted into accusations about unfair trade policies of various shapes and dimensions being used by Japan to keep US products out of the local market.

As the US manufacturing sector declined, the narrative was all about the evil restrictions that the Japanese were forcing onto US corporations attempting to trade in Japan, rather than focusing on the managerial decisions taken by the US corporations.

The Japanese responded simply by saying that Japanese consumers were disinterested in the large ‘yank tanks’ that the US corporations were trying to push into the domestic market.

Japanese consumers wanted small cars that were fuel-efficient and came with right-hand side steering.

The 2005 research by Donald Katzner and Mikhail Nikomarvo – Exercises in Futility: Post-War Automobile-Trade Negotiations between Japan and the United States – concluded that:

Indeed, the Big Three ignored the needs of both the Japanese and the United States car markets, and it was primarily this that prevented U.S. manufacturers from advancing in the Japanese auto market and allowed the Japanese automobile producers to establish a firm foothold in the United States …

Further, the US were oblivious to cultural aspects of Japanese life.

We learn that:

But apart from refusing to provide appropriate cars in the Japanese market, there was another reason why U.S. manufacturers were not selling many automobiles in Japan. For doing business successfully in Japan necessitates the establishment of long-term relations between manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers. That system is grounded in the obligation-and-loyalty fundamentals of Japanese culture … But American car manufacturers were not willing to take the time, energy, and money to enter into those relations in Japan and play the economic game according to Japanese rules.

The US corporations too quickly assume the role of the bully and think that everything revolves around their ‘exceptional’ products.

Well that approach was never going to work in Japan.

A recent article in the Japan Times (April 8, 2025) – The Japan tariff myth that just won’t die – carried the sub-title “It’s no mystery as to why Japanese streets are empty of U.S. cars”.

It concluded that:

That GM and Ford sell very little in Japan is true — GM shifted around 1,000 units in the fiscal year ended last month, with Ford at fewer than 200. Yet the belief that unfair trade practices are at fault isn’t only false, but also one of those enduring myths that refuses to die …

Tokyo hasn’t imposed tariffs on car imports since 1978. The country indeed had barriers to clear in the past, but those haven’t existed for years. Other impediments have been broken down since, leaving generations of lawmakers scratching their heads over U.S. complaints about market access. The source of their grievance is, in reality, something far simpler: The cars aren’t good enough.

American companies have simply failed to produce cars that appeal to local tastes. Japanese drivers want compact, fuel-efficient vehicles that balance excellent safety and reliability with superior value for money.

Management ineptitude is the reason the US car manufacturers cannot sell into Japan.

If you live in Japan for any period of time, it becomes obvious what the market for automobiles looks like.

Lots of those little rectangular cars buzzing around the narrow lanes and being squeezed into all sorts of tight parking spaces.

Most US cars simply would not fit down many of the Japanese streets.

In Australia, there is a debate that US manufacturers and their local importers are pushing where local authorities are being pressured to redefine parking spaces in our cities to fit the monstrous SUV obsession.

Japan will never have that debate.

Further, Japan has stricter automobile standards than the US, especially in relation to safety and emissions.

In Japan as in the EU and Australia and most places, a government agency provides the certification that new vehicles meet the required safety standards.

In the US, there is self-certification by the manufacturers.

US lobby groups also complain about Japan’s zoning rules for motor vehicle distribution and repair workshops, which are integral aspects of urban planning in Japan and help make their cities work better.

But, calling these so-called ‘non-tariff barriers’ a restraint on trade that have to be abandoned is nonsensical.

If the US had its way the rest of the world would engage in a race to the bottom on standards that Japan and other nations find essential to maintaining a quality society.

All manufacturers have to deal with these standards and regulations.

There is little evidence to support the claim that US manufacturers are discriminated against in this regard.

Companies like Mercedes, VW and BMW seem to be able to access the Japanese market in the highly selective ‘luxury car’ market.

The Japan Times article notes:

That’s why foreign brands dominate the luxury market: Mercedes-Benz Group sold more than 50,000 vehicles last year, while BMW and Volkswagen are also successful. While European cars have cultivated a high-end image, American cars come with an inferior reputation.

In closing, I thought this line from the Japan Times article was really good:

Ironically, it seems from complaints like Miller’s that the Trump administration, usually known for its opposition to diversity, equity and inclusion and other alleged “woke” initiatives, seems not to want equality of access — but rather equity in the form of equal outcomes.

Conclusion

The long-standing “Japan tariff myth that just won’t die” is just another example of the fake way the US attempts to bully other nations to give preferential treatment to US corporations.

In the case of Japan and the auto market – there is zero truth in the stuff that Trump and his mates are pumping out at present.

No surprise there though.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Leave a Reply