China’s economy is an unconventional mixture of central control and subsidies, especially involving the large state-owned firms and the financial sector, mixed with widespread use of privately owned firms and market mechanisms. One common mechanism has been to reward local government officials for meeting the goals that the central government has set for economic growth in their area. This arrangement can work reasonably well–right up to when it doesn’t.

Jeffery (Jinfan) Chang, Yuheng Wang, and Wei Xiong focus on this part of China’s economic story in “Taming Cycles: China’s Growth Targets and Macroeconomic Management” (Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring 2025). Here’s their description of the process of economic goal-setting across levels of China’s government.

From provinces, directly beneath the central government, down to cities, counties, and townships, each level of local government plays a crucial role in translating national targets into concrete economic outcomes. At the start of each year, local governments set their own growth targets in coordination with higher authorities, drawing on assessments of local economic conditions. A notable feature of this process is the phenomenon of “top-down amplification”—whereby national growth targets are consistently exceeded by provincial targets, which in turn are surpassed by city-level targets. This pattern reflects the incentive structure of China’s governance system, where local officials are assessed based on their ability to implement directives from higher authorities and drive economic growth within their jurisdictions. Consequently, regional leaders often set ambitious growth targets that exceed the expectations of their superiors. This strategy serves a dual purpose: providing a buffer to ensure compliance with higher-level expectations while also

motivating subordinates to outperform expectations. In this context, growth targets function not merely as planning tools but as instruments that foster competition among local governments. Our findings reveal a ratchet effect in how local governments adjust their growth targets asymmetrically—raising them aggressively during economic booms but lowering them more cautiously during slowdowns.

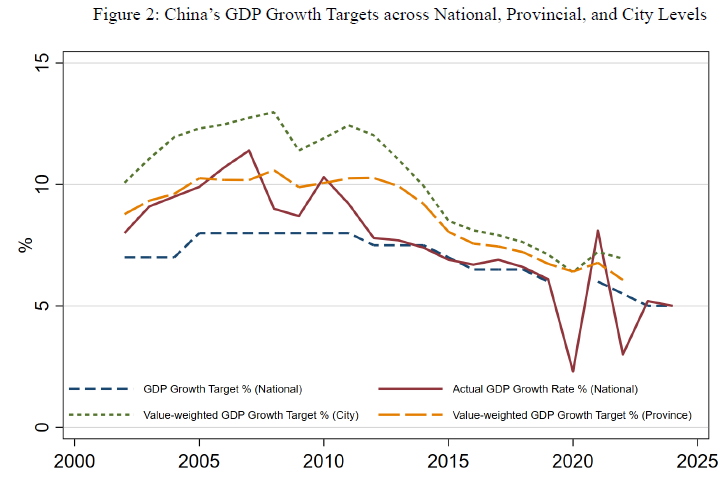

This figure illustrates the process in action. The dotted blue line is the national growth rate target. The red solid line is actual growth. The yellow dashed line is the province-level growth target (weighted by economic size of the province) and the green dashed line is the city-level growth target (weighte by economic size of the city).

As the authors point out, it’s useful to think of this figure as in two parts. In the first part, up through about 2010, the target rate for China’s growth is high and the actual growth rate is well above the target. Provinces and cities could set aggressive growth targets accordingly. But after about 2010, the real growth rate drops down to the national target, and the target itself is gradually reduced. The province- and city-level targets also come down, but more slowly.

An unwelcome dynamic emerges here. In the first decade or so of the figure, China’s growth was booming in substantial part as a result of an export surge, following China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001. Lower levels of government could compete with each other to facilitate this growth.

But consider the position of state and local governments as growth rates sag in the second part of the figure. Province- and city-level officials are being held responsible for meeting growth targets, and for them, the idea of proposing lower-level targes for growth is likely to sound dangerous. Many of them will look for ways to prop up the higher growth rates. The province- and city-level governments basically have two sources of funds to do this: land sales and borrowing. Indeed, one reason that China’s growth remained robust during the Great Recession of 2008 was that the central government gave lower levels of government permission to increase their borrowing–and in this way to stimulate their economies. The borrowed money was often used to build infrastructure, not necessarily because the infrastructure was needed, but just because the building itself counted as part of local economic growth for purposes of meeting the targets.

You can see where this is headed. The authors estimate that local-government debt, from 2011-19, grew by an amount equal to 14% of national GDP. The infrastructure that was built during this time was not reflected in greater revenue growth among publicly listed firms (which can be used as a proxy for the underlying economic growth beyond the government debt-induced sugar rush). The authors write:

The disconnect between GDP growth and broader economic indicators may stem from key mechanisms identified in studies of the Chinese economy. As infrastructure investment faced diminishing returns, large-scale projects likely failed to generate meaningful spillover effects (e.g., Qian, Ru, and Xiong, 2024). Meanwhile, the surge in local government debt crowded out capital that could have otherwise supported more productive private enterprises, hindering organic economic growth. This pattern aligns with findings from Cong and others (2019) and Huang, Pagano, and Panizza (2020) on the effects of China’s post-crisis stimulus.

To put it another way, local government officials under competitive pressure across areas to facilitate organic economic growth can be a useful development approach. But local government officials under competitive pressure to substitute for organic economic growth, by using debt to juice the local economy, will tend to leave behind a pile of questionable debt. Meanwhile, China’s official national growth targets were trending down, and how much to trust the official GDP statistics remains a very open question.

Leave a Reply